There’s a certain irony in the title of this post, as 2021 wasn’t a great year in some regards. Politics seemed crazy and crazier. People seemed to be getting over the virus, for the most part, but some were really sick or lost their lives. Healthcare providers seemed to get a handle on it, but not entirely. Oh, there were some bright spots in 2021, such as overall success for the stock market, and college football seemed almost normal.

And, entertainment, especially streaming video, always appreciated, became even more so. Everyone needs a break from reality. So, here’s some of the best books and shows I enjoyed in the past year:

On YouTube TV, hubby and I both very much enjoyed Yellowstone. This show is a modern western, with cowboys and rodeos, guns, big pickup trucks. The story reminds me of family shows of the past, such as “The Big Valley” which I saw in re-runs when I was much younger. However, the Dutton family is led by a patriarch instead of a matriarch, with Kevin Costner doing a fantastic job as the father of three grown children, and the head honcho of the ranch. His offspring are diverse and all interesting, if rather flawed. The Montana setting is certainly an important part of the series, and if you haven’t tried this show, unless you are extremely prudish or need a knight in shining armor to be the main character, I think you’ll like it.

Other streaming winners include the comedy series, Ted Lasso, which is now in its second season over on Apple TV, and Lost in Space in its third season on Netflix. Ted Lasso is a quirky story about an American football coach who is hired to coach a professional English soccer team. Lost in Space was originally a campy cult classic, but the modern iteration is more far more serious and has killer special effects along with good acting and quite a bit of suspense. The first season was amazing, the second season suffered from the sophomore blues, and season three is somewhere in the middle. Overall, it is one of the better space operas online, far surpassing any Trek or Star Wars recent entries that I have seen. (BTW, my son likes the Mandalorian, but I haven’t seen that, so the comment might not be entirely fair.)

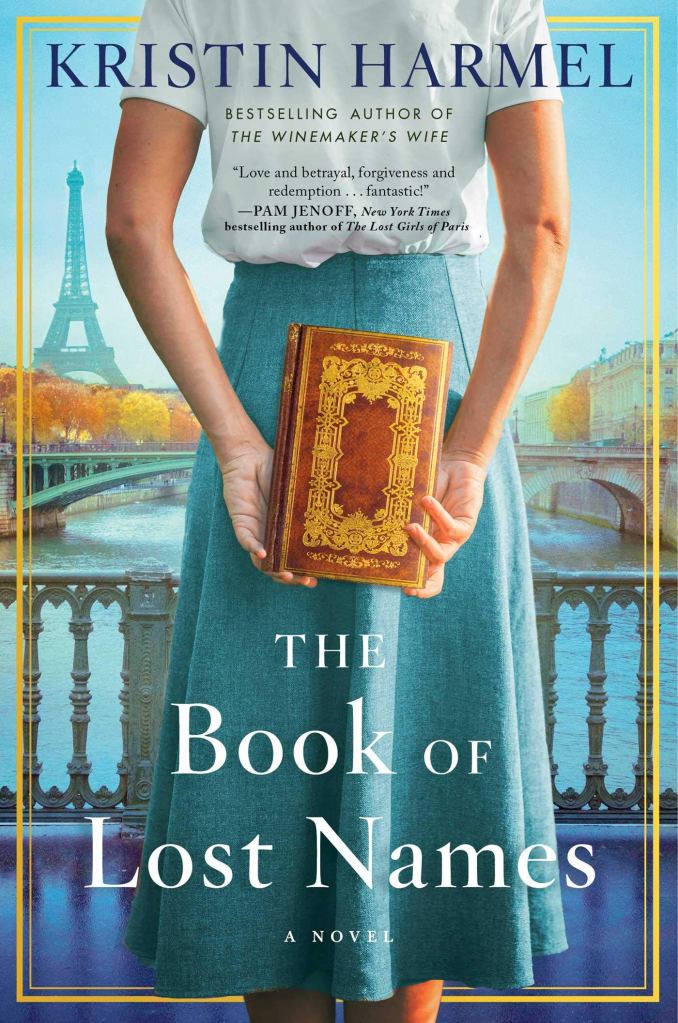

The best book I read in 2021 was probably The Book of Lost Names, by Kristin Harmel. This novel is set in set in Europe, during World War II. In The Book of Lost Names, the point of view character remains the same, but there are some deliberate time skips as the story moves from 2005, wherein the main character, Eva, is quite elderly, and 1942-46, when a young Eva spent several months forging documents in order to save people from the Germans who were occupying France (and threatening all of civilization.) Eva’s story is a real page turner, as there are moments of suspense, of hardship, and (thankfully) success, both in saving children from the Nazi war on Jews, and in Eva’s growing affection for a fellow member of the resistance. While I don’t want to include any spoilers, the book in the title refers to a code added to an existing book in the library of the local Catholic church, and the code included the real names of children who were perhaps too young to remember their birth names, which had to be altered so they could travel using forged documents.

Other good reads included Walter Issacson’s The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race, which I reviewed on this site. And, since I didn’t read them until 2021, I will mention Inside Marine One by Colonel Ray L’Heureux and Star Trek Voyager: A Celebration. None of the honorable mention books are fiction, which is rather unusual for me, as I am primarily a fiction reader. My most oft used source for fiction these days is a daily email from BookBub. Depending on the taste (or tolerance) of the reader, many eBooks are free or very low in price. Reading hasn’t been this cheap since I used to go to the public library every two weeks.

Inflation may be raging, but between streaming and eBooks, entertainment is fairly inexpensive these days. Gas and groceries are skyrocketing, but being entertained is fairly easy. Welcome, 2022!